China Historical Photos

@chinahistorypics.bsky.social

1.1K followers

3.4K following

520 posts

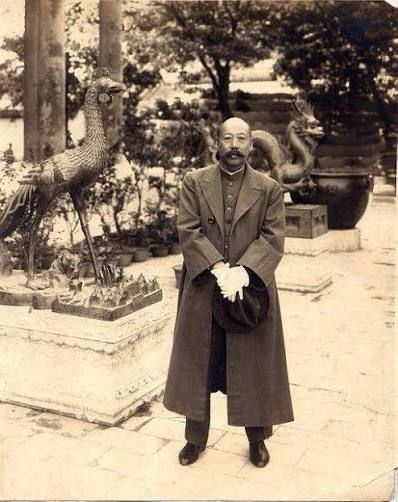

China’s story in pictures (1850–2000). From empire to revolution to reform—one photograph at a time.

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs