CMA: Islamic Art

@cmaislamic.bsky.social

870 followers

3 following

1.6K posts

Sharing public domain works from the Islamic Art department of the Cleveland Museum of Art.

Automated thanks to @andreitr.bsky.social and @botfrens.bsky.social

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

![This spectacular painting, both lyrical and fierce, comes from one of the greatest Iranian manuscripts ever produced. The royal copy of the national Iranian epic, the Shahnama, or Book of Kings, was made for Shah Tahmasp during the 1520s and 1540s. The book was even acclaimed in its own day for "the coloring and the portraiture" found in its 258 paintings. The lengendary hero Rustam, identified by his tiger-skin clothing, kills the savage chief of the demons, the White Div, in an immense cave, as other demons watch from above. Completing this last of seven trials, Rustam uses the White Div's blood to cure the Iranian king Kay Kavus of his blindness. The painting is set in a spectacular spring landscape with blossoming trees and brilliantly colored rocks that bend like spectators: They wrestled, tearing out each other's flesh, Till all the ground was puddled with their blood... [Rustam] reached out, clutched the Div, raised him neck-high, And dashed the life-breath from him on the ground, Then with a dagger stabbed him to the heart And plucked the liver from his swarthy form: The carcass filled the cave, and all the world Was like a sea of blood...](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:6xxjy3sxpdul5c74oh3ezlsi/bafkreib6pdwmhpok6ez3nstaqo4npm2tfc5zlque3tjikm4gn3cuwoe4iu@jpeg)

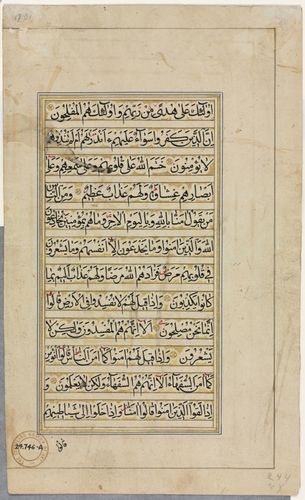

![Arabic inscriptions do not usually enhance albarellos, pottery jars for pharmacists. Here the elegant text reads: "Modesty [comes] from faith, and faith [comes] from Paradise," attributed to the Prophet Muhammad.](https://cdn.bsky.app/img/feed_thumbnail/plain/did:plc:6xxjy3sxpdul5c74oh3ezlsi/bafkreiagb5mzedllpznja5fidtchs4g4dvoj7wvdfsmcoeq5zut43uc7ei@jpeg)