Dan Garisto

@dangaristo.bsky.social

5.2K followers

300 following

1K posts

science journalist | good physics, bad physics, and sometimes ugly physics

Signal: dgaristo.72

Email: [email protected]

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

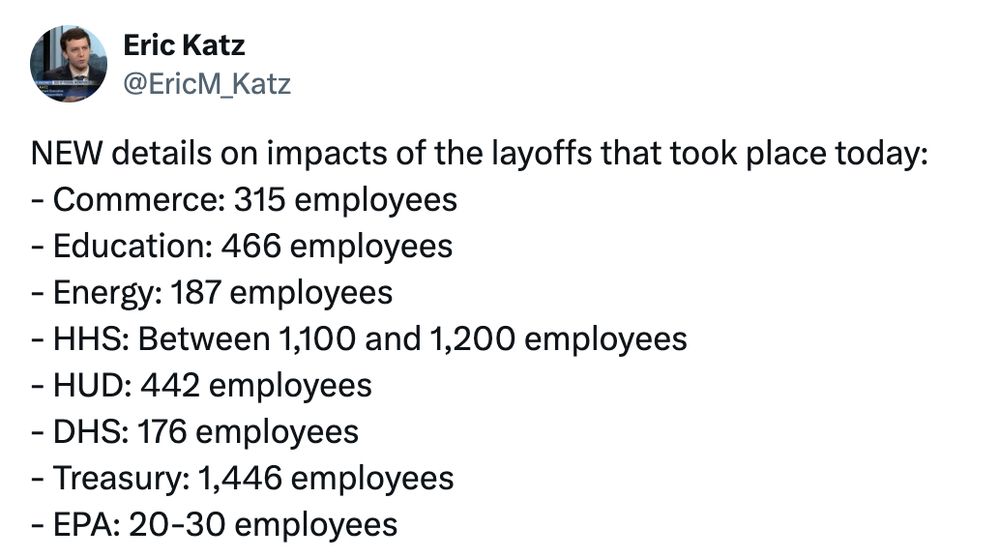

Reposted by Dan Garisto

Reposted by Dan Garisto