Our World in Data

@ourworldindata.org

44K followers

17 following

2K posts

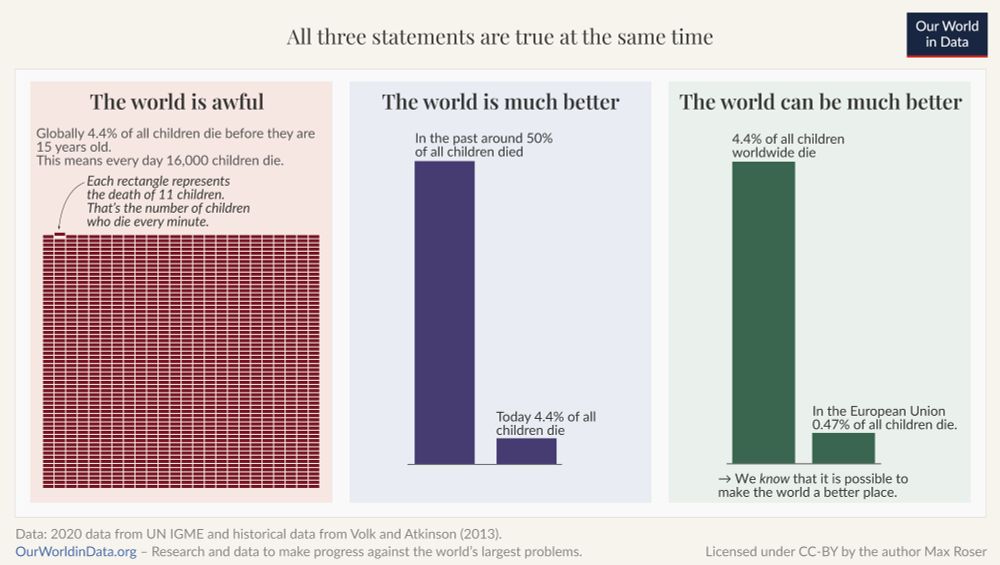

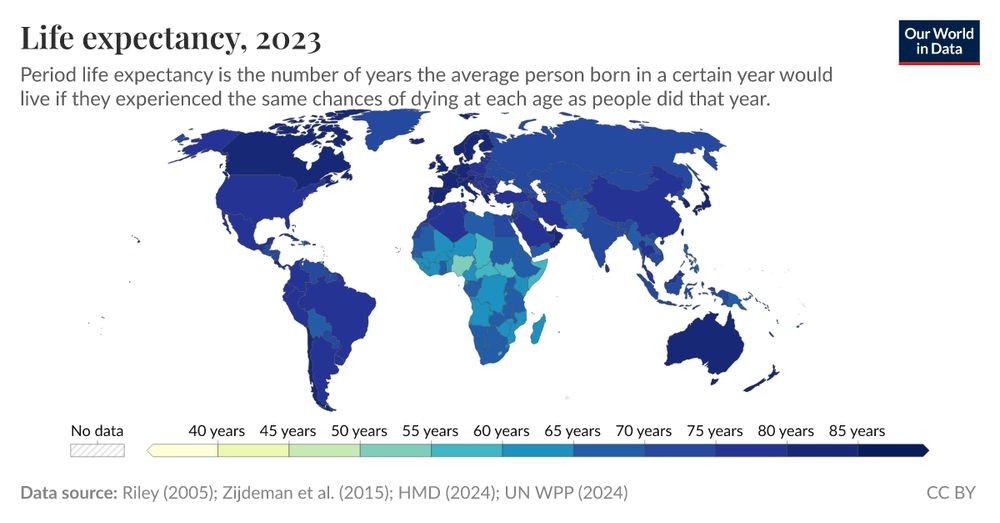

Research and data to make progress against the world’s largest problems. Based out of Oxford University (@ox.ac.uk), founded by @maxroser.bsky.social.

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

Pinned