www.brookings.edu/articles/wil...

www.brookings.edu/articles/wil...

bsky.app/profile/matt...

bsky.app/profile/matt...

Pinging Equifax's The Work Number — which states are likely to rely on to get recent-enough employment data — "sometimes costs over $20 per person per query"

Pinging Equifax's The Work Number — which states are likely to rely on to get recent-enough employment data — "sometimes costs over $20 per person per query"

bsky.app/profile/matt...

bsky.app/profile/matt...

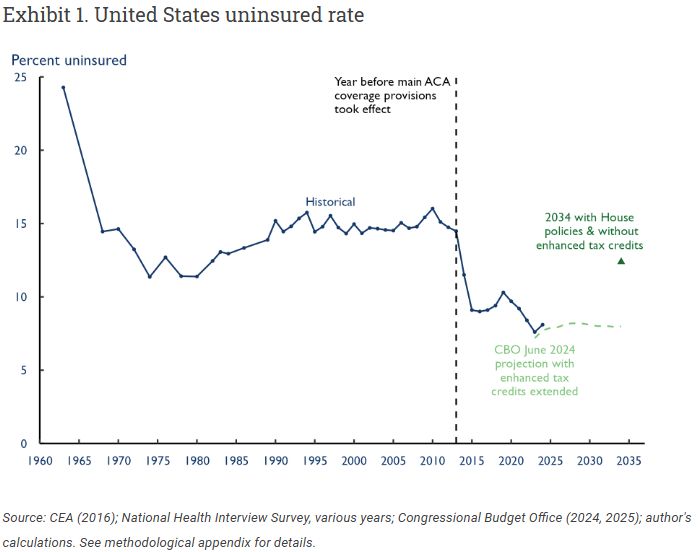

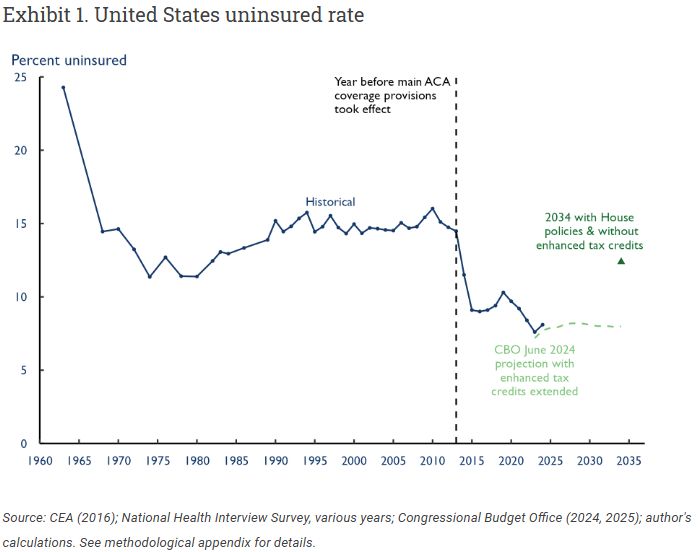

-- @mattafiedler.bsky.social www.healthaffairs.org/content/fore...

-- @mattafiedler.bsky.social www.healthaffairs.org/content/fore...

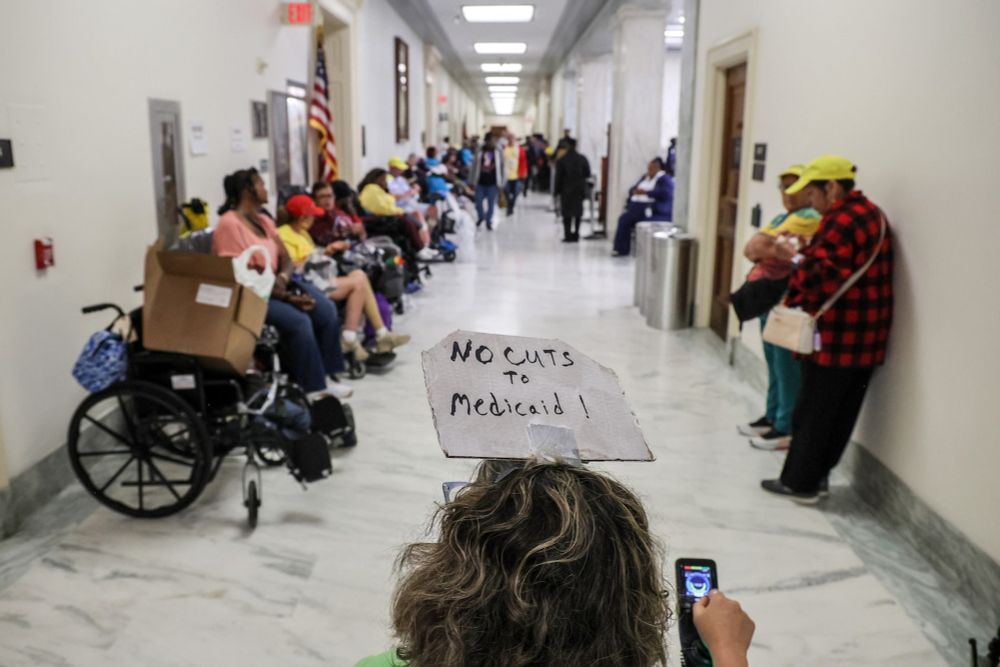

But who loses benefits and what happens if work requirements are reversed?

New evidence from linked SNAP-Medicaid data and a natural experiment in CT tell a concerning story...

Thread below 👇

But who loses benefits and what happens if work requirements are reversed?

New evidence from linked SNAP-Medicaid data and a natural experiment in CT tell a concerning story...

Thread below 👇

www.cms.gov/newsroom/pre...

www.cms.gov/newsroom/pre...

One big difference, which could matter politically: No explicit rollback of pre-existing condition protections.

www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/202...

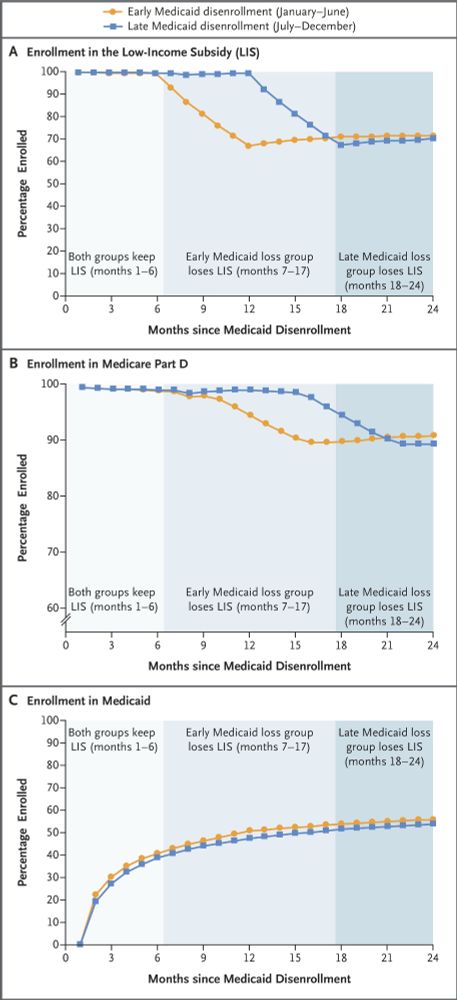

Medicare saves lives. But is it enough to save lives of the most vulnerable Americans? The study suggests no; Medicaid still matters. (1/11)

Medicare saves lives. But is it enough to save lives of the most vulnerable Americans? The study suggests no; Medicaid still matters. (1/11)

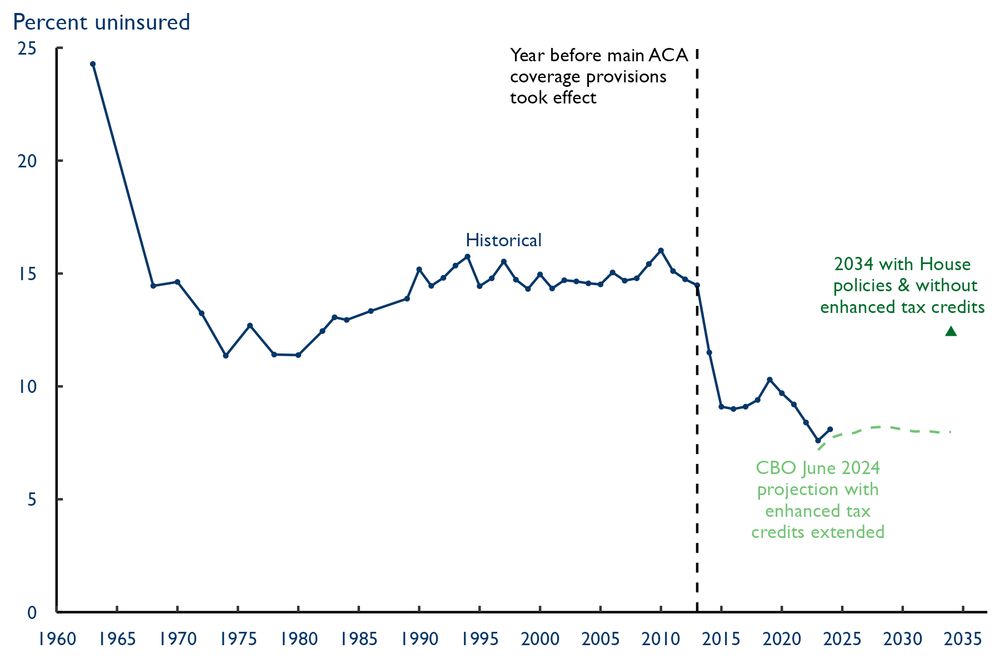

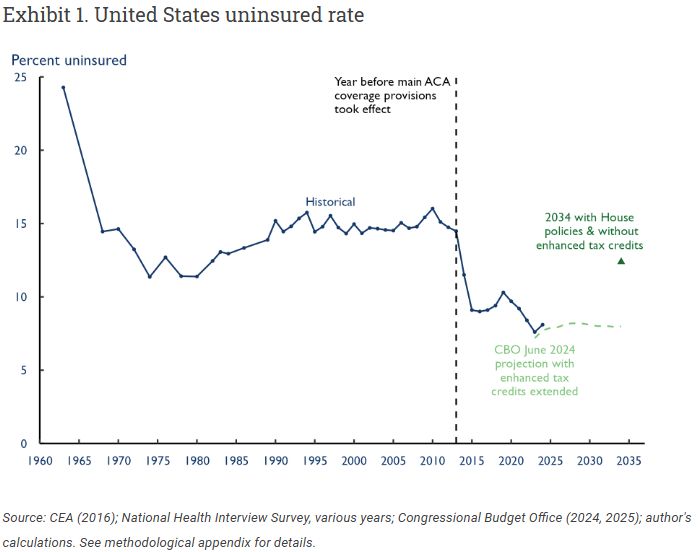

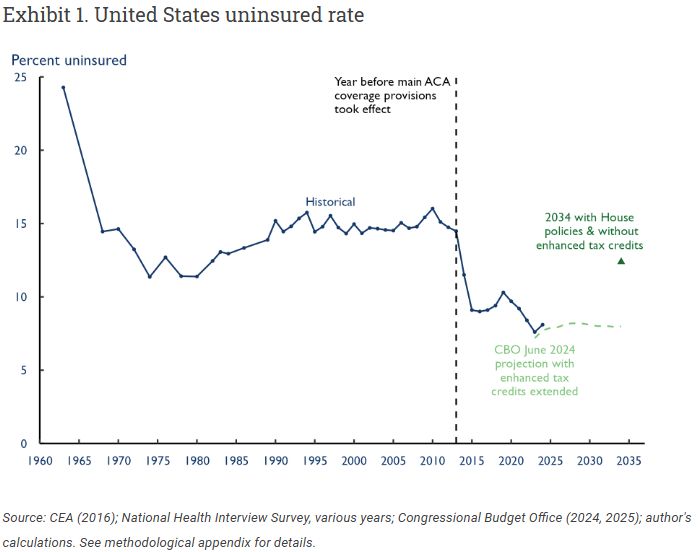

Must-read @mattafiedler.bsky.social @lorenadler.bsky.social on House Republican cuts to Medicaid and the ACA www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/202...

Must-read @mattafiedler.bsky.social @lorenadler.bsky.social on House Republican cuts to Medicaid and the ACA www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/202...

My new paper looks back at an Arkansas requirement very similar to one the House passed in 2023.

I estimate an Arkansas-like policy would reduce Medicaid enrollment for ppl subject to it by 34% in the long run:

My new paper looks back at an Arkansas requirement very similar to one the House passed in 2023.

I estimate an Arkansas-like policy would reduce Medicaid enrollment for ppl subject to it by 34% in the long run:

That's actually code for a big cut -- and taking out a piece of the ACA with it

My latest at @thebulwark.bsky.social

www.thebulwark.com/p/health-ins...

That's actually code for a big cut -- and taking out a piece of the ACA with it

My latest at @thebulwark.bsky.social

www.thebulwark.com/p/health-ins...

FMAP is calculated according to a formula in statute, which enforces a floor of 50% and a ceiling of 83% match.

Louisiana is only paying 32 cents on the dollar.

Not surprising given that he helped write the Graham-Cassidy Medicaid destruction plan in 2017.

Expect to see more of this from Rs - but don’t be fooled: cutting money to states to run Medicaid means people lose coverage and benefits.

FMAP is calculated according to a formula in statute, which enforces a floor of 50% and a ceiling of 83% match.

Louisiana is only paying 32 cents on the dollar.