📷 Sick Whooper Swan by Kane Brides

#UKBirding #BirdingWales #BirdingScotland

Change over time plots: stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_tota...

Spatial trends maps (ringing only): stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_map/

Change over time plots: stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_tota...

Spatial trends maps (ringing only): stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_map/

www.linkedin.com/pulse/icelan...

www.linkedin.com/pulse/icelan...

I'm excited to announce that the theme of the 2027 BOU conference is Avian Disease Ecology!

📍 Nottingham, UK

📅 6–8 April 2027

🔗 Full details: lnkd.in/gPvFFDJe

Please share widely!

#BOU2027 #Ornithology #WildlifeDisease #AvianDisease #EcoHealth

I'm excited to announce that the theme of the 2027 BOU conference is Avian Disease Ecology!

📍 Nottingham, UK

📅 6–8 April 2027

🔗 Full details: lnkd.in/gPvFFDJe

Please share widely!

#BOU2027 #Ornithology #WildlifeDisease #AvianDisease #EcoHealth

Huge thanks to all involved!

www.nature.com/articles/s41...

Huge thanks to all involved!

www.nature.com/articles/s41...

We link this to social learning in novel migration route development.

rdcu.be/d57Mw

1/10

#ornithology

We link this to social learning in novel migration route development.

rdcu.be/d57Mw

1/10

#ornithology

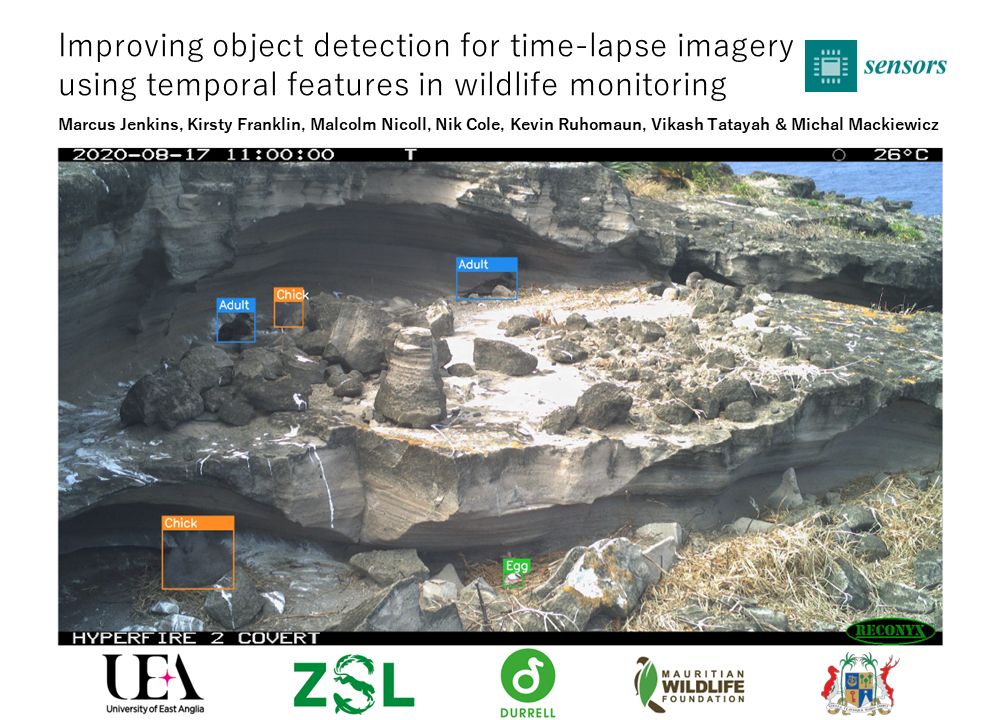

Proud of this collaboration with UEA Computing Sciences' Marcus Jenkins & Michal Mackiewicz to improve object detection for time-lapse imagery using temporal features. 📷🖥️⏲️

Open Access in Sensors: mdpi.com/3088004

Proud of this collaboration with UEA Computing Sciences' Marcus Jenkins & Michal Mackiewicz to improve object detection for time-lapse imagery using temporal features. 📷🖥️⏲️

Open Access in Sensors: mdpi.com/3088004

Come work on a super fascinating system: partial #migration in European shags. #Fieldwork, theoretical #modelling and #QuantitativeGenetics are all possible depending on interests. Please spread to good candidates of any nationality! www.jobbnorge.no/en/available...

Come work on a super fascinating system: partial #migration in European shags. #Fieldwork, theoretical #modelling and #QuantitativeGenetics are all possible depending on interests. Please spread to good candidates of any nationality! www.jobbnorge.no/en/available...

Explore graphs of numbers ringed etc. and NRS records over time:

stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_tota...

Explore a map of numbers ringed, etc. by region:

stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_map/

Explore graphs of numbers ringed etc. and NRS records over time:

stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_tota...

Explore a map of numbers ringed, etc. by region:

stephenvickers.shinyapps.io/ringing_map/

royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/...

1/8

#ornithology 🐦

royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/...

1/8

#ornithology 🐦