Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

800 followers

190 following

47 posts

Economist and professor at the University of Virginia.

www.alexandermackay.org

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 19

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 19

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 19

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 19

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 19

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 11

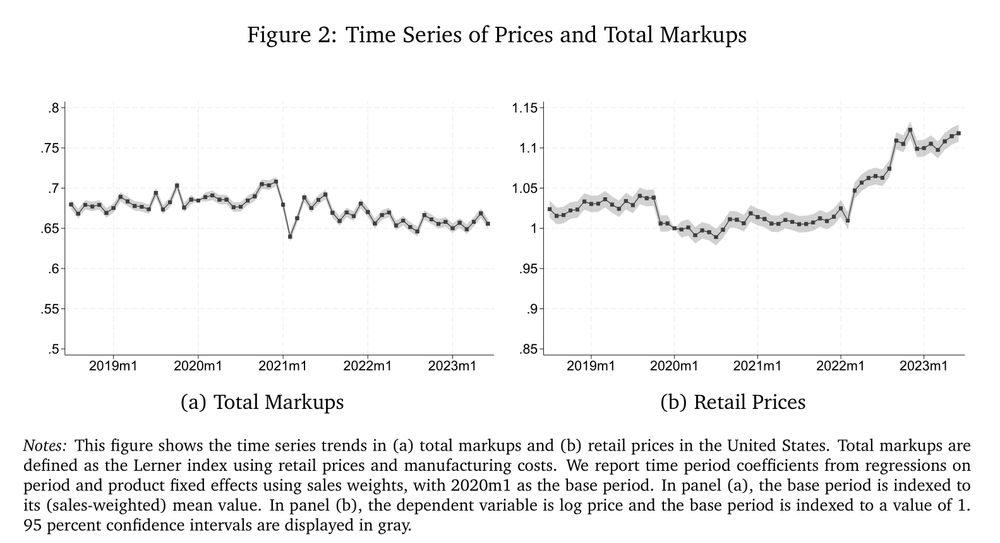

Markups and Cost Pass-through Along the Supply Chain

Founded in 1920, the NBER is a private, non-profit, non-partisan organization dedicated to conducting economic research and to disseminating research findings among academics, public policy makers, an...

nber.org

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 11

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· Aug 11

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· May 28

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· May 27

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· May 27

Alex MacKay

@amackay.bsky.social

· May 27