Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

87 followers

78 following

12 posts

Harvard Government PhD candidate, interested in structural origins of political outcomes.

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

Pinned

Reposted by Noah Dasanaike

Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

· Feb 14

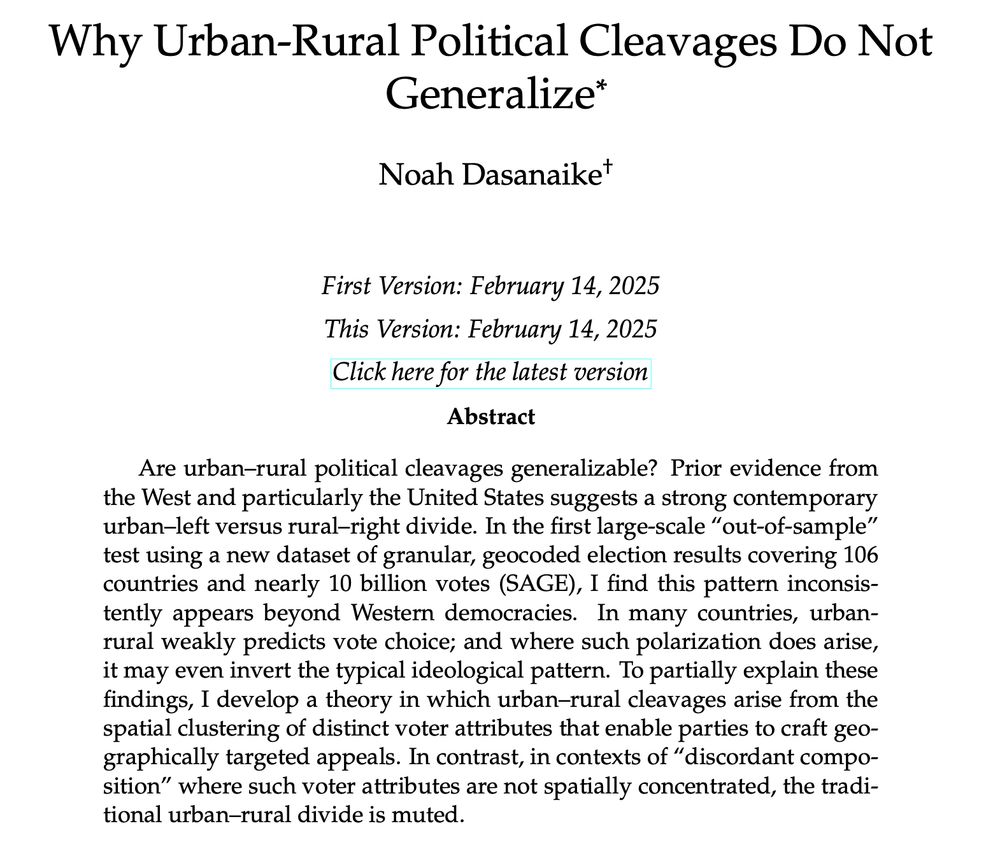

Release Notification: Small-Area Global Elections (SAGE) archive

Sign up to receive email notification of when SAGE is released alongside the corresponding paper, Why Urban-Rural Political Cleavages Do Not Generalize (working paper found here, with country-by-count...

shorturl.at

Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

· Feb 14

Release Notification: Small-Area Global Elections (SAGE) archive

Sign up to receive email notification of when SAGE is released alongside the corresponding paper, Why Urban-Rural Political Cleavages Do Not Generalize (working paper found here, with country-by-count...

shorturl.at

Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

· Feb 14

Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

· Feb 14

Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

· Feb 14

Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

· Feb 14

Noah Dasanaike

@noahdasanaike.bsky.social

· Feb 14