Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

120 followers

160 following

14 posts

Researcher: Computational Social Science, Text as Data

On the job market in Fall 2025!

Currently a Postdoctoral Research Associate at Network Science Institute, Northeastern University

Website: pranav-goel.github.io/

Posts

Media

Videos

Starter Packs

Reposted by Pranav Goel

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

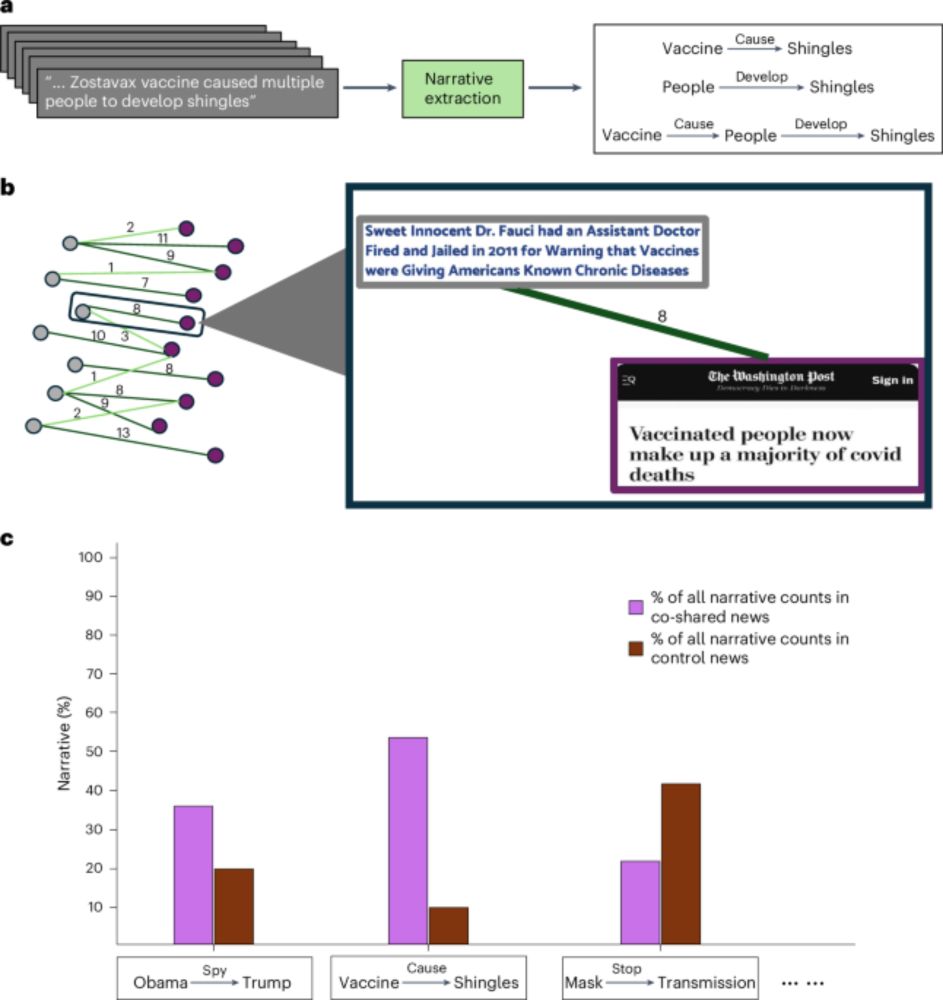

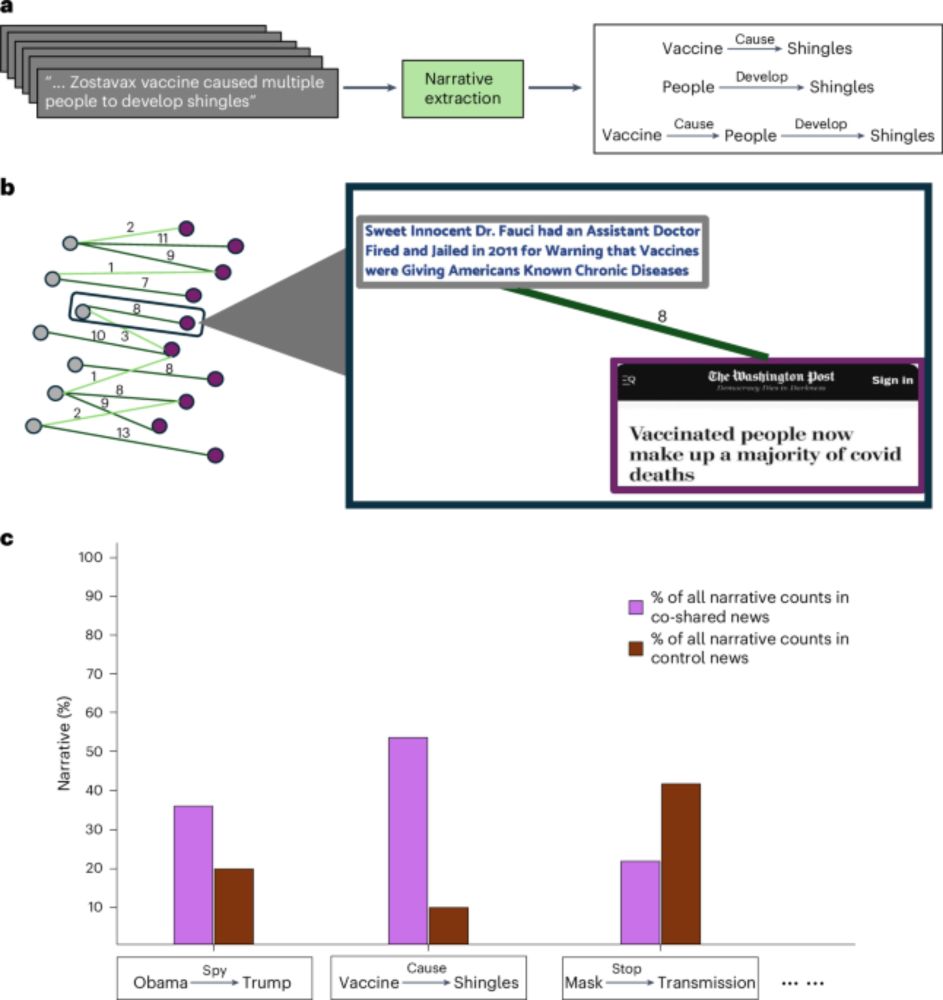

Using co-sharing to identify use of mainstream news for promoting potentially misleading narratives - Nature Human Behaviour

Goel et al. examine why some factually correct news articles are often shared by users who also shared fake news articles on social media.

nature.com

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Jun 11

Reposted by Pranav Goel

David Lazer

@davidlazer.bsky.social

· May 15

Reposted by Pranav Goel

Pranav Goel

@pranavgoel.bsky.social

· Feb 18