Ecological strategies to end the war on resistance

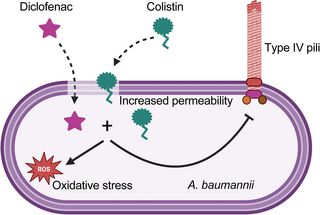

Military metaphors are pervasive in the language of antibiotics and resistance [1]. Bacterial pathogens are foreign invaders with whom we are at war. To fight them, we deploy antibiotic chemical weapons. Powerful antibiotics are big guns, narrow-spectrum antibiotics are silver bullets, and broad-spectrum antibiotics are nuclear bombs. We are in a losing battle against antibiotic-resistant superbugs and are quickly running out of ammunition. Metaphors shape how you feel about an issue, and how you feel often determines the actions you take. Framing resistant bacteria as foes to be feared traps us within a fundamentally adversarial us-versus-them framework, where the only possible outcomes are their eradication—or ours.Instead, a growing body of research is re-examining antibiotic resistance through the lens of microbial ecology and evolution. This work has revealed that bacterial resistance significantly predates human use of modern antibiotics, with resistance genes encoded by many benign environmental and commensal microbes often before they are detected in pathogens [2]. Unchecked antibiotic use can dramatically amplify these resistance reservoirs, select for their dissemination into pathogens, and engender significant negative side effects on human health [3,4]. Given the dwindling approval of new antibiotics [5], we must rethink the brute force approaches that attempt (futilely) to fight resistance by searching for the next bacteria-killing molecule. Instead, we should pursue complementary strategies that mitigate selection of antibiotic resistance by improving stewardship and developing novel chemotherapeutic, probiotic, and prebiotic strategies for suppressing bacterial virulence and supporting commensalism.To contrast the military metaphors, we metaphorize these ecological approaches using the diplomatic terms of disarmament, nonproliferation, and soft power. Strategies for targeted killing of pathogens must invariably remain part of our medical toolkit, but by pursuing these complementary strategies, we argue that we can better foster sustainable coexistence with our microbial cohabitants and tip the scales against pathogenesis.Ancient originsMost of our clinically important antibiotics were discovered as the natural products of soil-dwelling microbes, particularly the actinomycetes. In 1973, Davies and Benveniste [6] proposed that the origins of antibiotic resistance likely lie with these ‘producer’ microbes, as they would need elements to protect themselves from the antibiotics they produced. These elements, by definition, would be antibiotic resistance genes. The producer hypothesis postulates that, over time, nonproducers (including pathogens) have acquired these antibiotic resistance genes via horizontal gene transfer. With the evolution of antibiotic production estimated to have occurred hundreds of millions of years ago [7], antibiotic resistance must be just as old.The ancient origin of resistance in soil-dwelling microbes explains several features of resistance that seem puzzling, even paradoxical, when viewed solely from a clinical perspective. First, it explains why soil-dwelling actinomycetes encode resistance to more antibiotics than most clinical pathogens; seven or eight antibiotics on average and 15 at the upper end, including synthetic compounds recently approved for clinical use [8]. It also explains why soils are an immense and diverse reservoir of previously unknown resistance genes not yet seen in pathogens, and how soil bacteria and human pathogens can encode identical resistance genes [9].Collateral damageZooming in on the subset of antibiotic-resistant bacteria associated with humans, an ecological perspective also reveals the unintended knock-on effects of antibiotic use. Pathogens are not the only microorganisms that make a home in the human body. Each human is colonized by 500 to 1000 species of bacteria, and the number of bacterial cells is roughly the same as the number of human cells [10,11]. These microbes form relatively stable ecosystems called microbiomes, which are just as diverse and complex as macroscopic ecosystems. The densest and most diverse human-associated microbiome is in the colon: the gut microbiome. A healthy gut microbiome is critical to human health and development, providing essential functions including nutrient processing, colonization resistance against pathogens, and immune system regulation [12].Antibiotics are developed with the intention of killing a select few pathogenic species; however, they do so by targeting conserved molecular features shared by thousands of species across broad branches of the tree of life (e.g. cell wall, ribosome, and RNA polymerase). As a result, they can indiscriminately kill both ‘good’ commensal species and ‘bad’ pathogens when administered to humans. Taking antibiotics to treat a gut infection may kill the pathogen, but at the cost of potential significant collateral damage—another military metaphor—to commensal microbiota. Substantial antibiotic perturbations can lead to microbiome dysbiosis, characterized by acute or persistent imbalanced states of the commensal ecosystem. Dysbiosis has been associated with numerous human pathologies, including inflammatory bowel disease, obesity, and gastrointestinal cancers [13]. Postantibiotic microbiome dysbiosis can also lead to the expansion of opportunistic pathogens in the gut, such as Clostridioides difficile.Antibiotic use also contributes to antibiotic-resistant bacteria within the gut microbiome. In the context of war, killing any number of the enemy seems like a victory; however, like a hydra sprouting two heads after one is chopped off, repeated antibiotic exposures will make antibiotic-resistant bacteria stronger [14]. Importantly, this is not limited to pathogens. The same evolutionary dynamics of selection and adaptation also drive increasing resistance in nonpathogenic species. Often, this resistance is encoded on mobile genetic elements, which can lead to more frequent and broader dissemination of resistance by horizontal gene transfer.Diplomatic strategiesNo matter how many bacteria-inhibiting drugs we develop, antibiotic resistance is never going away. The history of antibiotic use and resistance in pathogens has taught us that resistance is not a question of ‘if,’ but rather, only a matter of ‘when’ [15]. Instead, we must develop complementary strategies that enable us to better coexist with resistant bacteria while suppressing their virulence. New approaches draw on two key insights from microbial ecology: first, the real problem is not resistance alone, but resistance coupled with pathogenesis. Second, pathogenesis is not binary between ‘good’ commensals and ‘bad’ pathogens but a spectrum between them. For example, pathobionts like Escherichia coli can be harmless members of a healthy gut microbiome or a disease-causing gastrointestinal, urinary, or blood pathogen, depending on the host and environmental context, and the induced expression of specific repertoires of virulence factors. In contrast to the martial strategies of conventional antibiotic deployment for bacterial growth inhibition or killing, ecology-first strategies borrow from tenets of diplomacy and cooperation to attempt to mitigate antibiotic resistance by tilting bacteria away from pathogenesis toward avirulence and commensalism.De-escalation (antibiotic stewardship)The back-and-forth between humans deploying new antibiotic drug classes and bacteria evolving new resistance mechanisms has been called an evolutionary arms race. That implies bacteria are a strategic enemy consciously responding to our moves with countermoves; however, the expansion and spread of resistance is an automatic evolutionary response to the selective pressure imposed on bacteria by prolific antibiotic use. The development of more powerful antibiotics to eradicate resistant bacteria continues to escalate the antibiotic arms race. Instead, we should strive for de-escalation by controlling and reducing antibiotic use.In clinical settings, stewardship programmes encourage prudent use of antibiotics. They establish guidelines for ‘the optimal selection, dosage, and duration of antimicrobial treatment that results in the best clinical outcome for the treatment or prevention of infection, with minimal toxicity to the patient and minimal impact on subsequent resistance’ [16]. In conjunction, it is critical to reduce antibiotic overuse and misuse. Overuse occurs when antibiotics are used unnecessarily, such as in patients with viral infections, noninfectious processes, bacterial infections that do not require antibiotics, and bacterial colonization [17]. It also occurs when medically important antibiotics (i.e. from classes important to human medicine) are used in food-producing animals to improve growth rates [18]. Antibiotics are also frequently misused, such as when broad-spectrum antibiotics continue to be used even after culture data indicates the pathogen is not susceptible to that regimen or a narrower-spectrum compound would be just as effective. Phage therapy, which kills antibiotic-resistant pathogens using highly specific bacteriophages, is also a promising alternative to traditional antibiotics.Disarmament (antivirulence)At its root, the problem with antibiotic-resistant infections is not resistance per se but pathogenesis. An alternative to antibiotics are antivirulence therapeutics that disarm pathogens of the virulence factors pathogens produce to cause infection and evade the host immune response (e.g. toxins, adhesins, immune evasion and modulation factors, and siderophores) [19,20]. Interestingly, antivirulence strategies historically precede antibiotic use, with Emil von Behring developing an antiserum directed against diphtheria toxin in 1893. A related strategy, referred to as plasmid interference and plasmid curing, disarms pathogens at the genetic level by eliminating problematic plasmids that encode for virulence and antibiotic resistance genes [21,22].These approaches have several distinct advantages compared with conventional antibiotics: first, because commensal bacteria generally do not encode for virulence factors, there is less potential impact on the broader gut microbiome. Second, although antibiotics target central growth pathways, these strategies do not destroy host bacterial populations outright. That may mean there may be less evolutionary pressure for the development of antivirulence and plasmid-curing resistance. Although several antivirulence agents have entered clinical trials, most are still in the preclinical stage [20].Soft power (colonization resistance)Whether a pathobiont is a virulent pathogen or a benign commensal can depend on its ecological context. Commensal microbiota can suppress the proliferation of incoming pathogens and the expansion of opportunistic pathobionts via several mechanisms of colonization resistance. These include nutrient competition, altering host environmental conditions, and enhancing the intestinal epithelial barrier [23]. By modulating the gut microbiome using probiotics and prebiotics, or replacing dysbiotic microbiota with those from healthy donors through faecal microbiota transplantation, we can exert a kind of soft power that influences pathobionts to adopt commensal lifestyles, rather than pathogenic ones.For example, patients can be asymptomatically colonized for prolonged periods by toxigenic C. difficile. Our recent work has identified certain commensal gut species that protect against disease by suppressing C. difficile toxin production while allowing its stable growth and colonization in the gut [24]. By identifying such commensal-pathogen dynamics, we can design microbiome-targeting therapeutics that alter the gut microbiome in a way that steers pathogens toward avirulent states.ConclusionLike any good diplomatic strategy, the best approach to mitigate antibiotic resistance will be multipronged. When used in combination, many of the approaches above could reinforce each other: reducing antibiotic use increases the gut microbiome’s colonization resistance against C. difficile and neutralizing the C. difficile toxins with antivirulence drugs bolsters the action of commensal species that suppress toxin production. Similar approaches may also be used beyond the gut microbiome to address antibiotic-resistant infections from the oral, skin, and genital microbiomes. However, we stress that although they are frequently based on well-established ecological principles and in vivo studies, the therapeutic potential of these approaches remains speculative. Few have been proven in the field and, if implemented, should be tailored to the specifics of each patient, pathogen, and disease.We likely will always need targeted antibiotics to kill the deadliest human pathogens, especially in immunologically vulnerable patients. However, as in human diplomacy, we must strive to explore all other options to suppress pathogenesis and only resort to armed conflict as a last resort. Nonantibiotic strategies of de-escalation, disarmament, and soft power promise to be effective for patients in the short term while conserving our antibiotic arsenal for those who need it most. By understanding and leveraging the ecological and evolutionary processes underlying antibiotic resistance, pathogenesis, and commensalism, we may be able to more sustainably and peacefully coexist with the diversity of microbes who live in and on us.CRediT authorship contribution statementKevin S. Blake: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Gautam Dantas: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.Declaration of competing interestThe authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.AcknowledgementsWork in the authors’ laboratory was supported in part by awards to G.D. through the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID; award numbers U01AI123394, R01AI155893, R01AI184858), and the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH; award number U01AT012998) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH).