My Chinese school made a fun video about my Chinese learning journey. Don’t judge the pronunciation, it was filmed in 2023! 🙈

youtube.com/watch?v=Ay4D...

youtube.com/watch?v=Ay4D...

Dr. David Broockman's Learning Journey (Chinese-Speaking Version)

YouTube video by Chinese Language Academy

m.youtube.com

by Anne Applebaum — Reposted by: David Broockman, Jesse H. Kroll, Karen R. Lips , and 1 more David Broockman, Jesse H. Kroll, Karen R. Lips, Paul L. Morgan

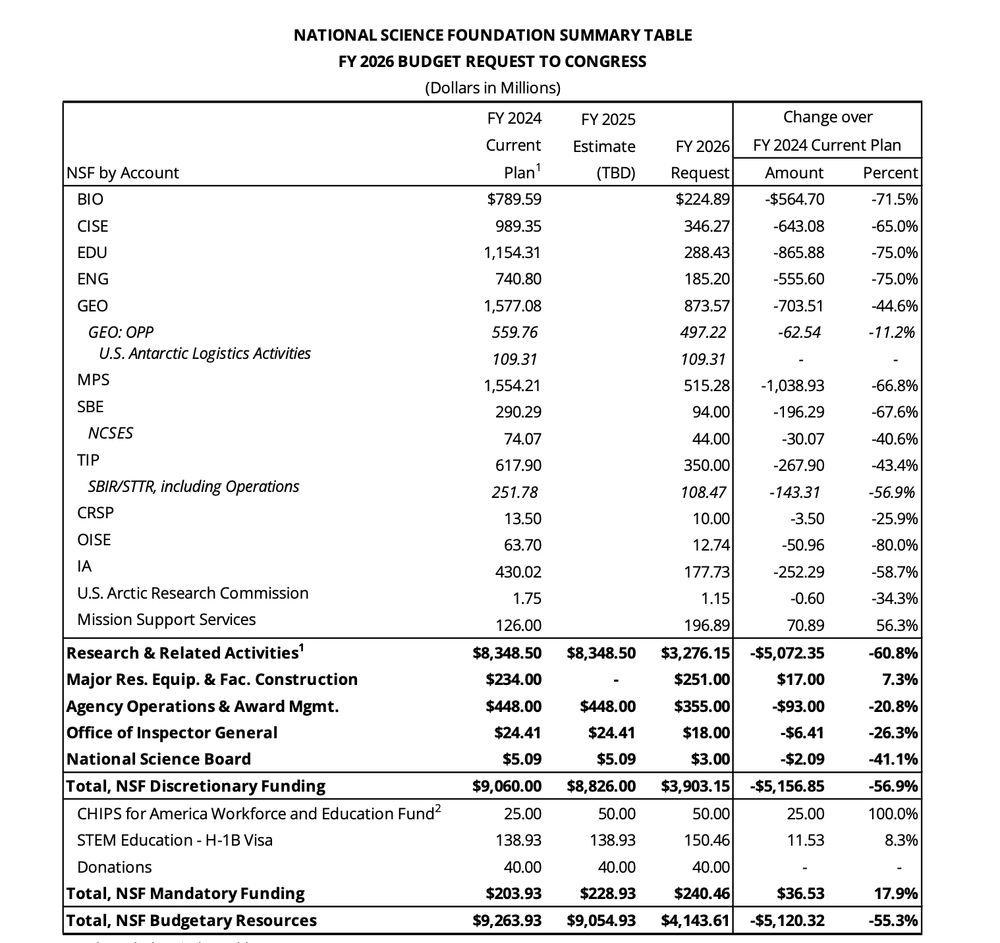

Presidential budget is out. Here's NSF. Biggest cut, by amount, is $1 billion, or 66.8%, from MPS (Physics & Math directorate). nsf-gov-resources.nsf.gov/files/00-NSF...

Will add this to our list to look at! We do have candidate fixed effects so our main specification shouldn't contain any bias from that.

Yes, you can see some of the partisan asymmetry in Fig 1 -- R candidates are much more right than D candidates are left. Ds are to the left of voters, still, but voters see the Ds as even more left than they are -- sign of how the national party brand needs to improve.

Thanks for your questions! Fig 2 has endorsement knowledge -- in primaries it's much higher than policy position knowledge. Endorsements often go to different cands; we should quantify this. And I'll see if we have data on timing!

I'd put my money down for a revised version of #1: moderation on issues where your party is out of step

Some caveats: This is observational data from 27 districts in 2024. Voters might care about other things like compromise or ideology that we didn't study. For issue voting, projection is a threat to causal inference–but we discuss why that’s unlikely to explain our findings.

Parties face a dilemma. Nominating moderates in close districts helps win—but most voters infer that candidates hold the party’s typical positions. To win some seats, a party needs a *nationwide* moderate reputation. But groups & others might not want to build it (e.g., by moderates in safe seats).

Summarizing: primary voters actually struggle to identify which candidates match their views. So they rely on other cues—especially from interest groups who might help drive polarization. But general election voters then *do* punish extremism.

FINDING #3: Evidence that groups contribute to polarization. Group endorsements have major influence. Voters who learn about them are ~15 pp more likely to vote for endorsed candidates. This effect is driven by endorsements from liked groups—negative cues barely register.

This creates a problem for primary voters: party cues are useless in primaries where everyone's the same party. So primary voters stay confused about who's closest to them, even as they learn what candidates of their party stand for.

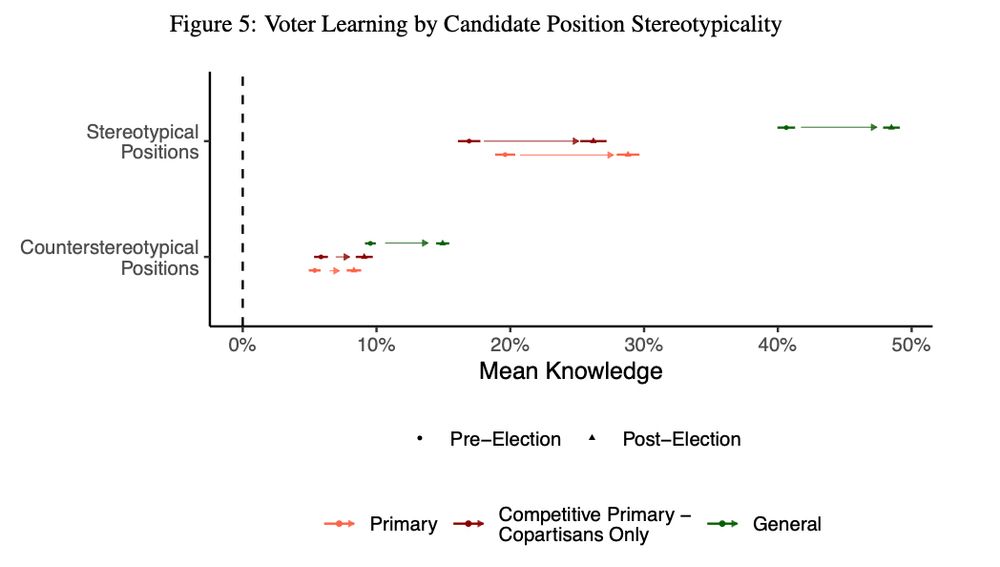

We found evidence that voters learn about candidates partly by learning national party reputations: a) voters somehow learn just as much about no-name candidates, & b) voters are 3x more likely to learn "stereotypical" positions (like Dems supporting healthcare) than unusual ones

Why do general election voters know more? Party cues.

In general elections, party labels give voters huge clues about candidate positions. In primaries, all candidates have the same party label—so these cues are useless for choosing between them.

In general elections, party labels give voters huge clues about candidate positions. In primaries, all candidates have the same party label—so these cues are useless for choosing between them.

BUT: b/c they know more, general voters much more successfully identify the closest candidate. They vote for the closest candidate on an issue 78% of the time; primary voters only do 18% of the time

The opposite of conventional wisdom about incompetent general voters & aware primary voters

The opposite of conventional wisdom about incompetent general voters & aware primary voters

When primary AND general voters learn a candidate agrees with them on an issue, they're ~14 percentage points more likely to vote for that candidate.

In generals, this includes when the closest candidate is an outpartisan–party loyalty isn’t everything.

In generals, this includes when the closest candidate is an outpartisan–party loyalty isn’t everything.

FINDING #2: Using Lenz’s identification strategy and exploiting our panel data, we also estimate issue voting.

Both primary AND general election voters change their votes when they learn candidate positions—by a very similar amount…

Both primary AND general election voters change their votes when they learn candidate positions—by a very similar amount…

FINDING #1: General election voters know MORE about candidate positions than primary voters.

By election day, general election voters correctly identify 40% of candidate positions vs just 22% for primary voters.

By election day, general election voters correctly identify 40% of candidate positions vs just 22% for primary voters.

This gives us a ton of unique data.

We measure knowledge & learning of 122 candidate issue positions in the 2024 Congressional primaries and 269 candidate issue positions in the 2024 Congressional generals.

We measure knowledge & learning of 122 candidate issue positions in the 2024 Congressional primaries and 269 candidate issue positions in the 2024 Congressional generals.

We monitored debates, websites, & news in real time during the 2024 primary and general elections to identify issues & endorsements where the candidates *in each district* differed. We then conducted pre-election surveys 2-3 mo before each election & re-surveyed again on e-day.

Conventional wisdom blames:

• Primary voters who closely follow politics & prefer extremists

• General election voters who are too ignorant of candidate positions—or too “intoxicated” by party loyalty—to vote for moderates over extremists

But our data tells a different story…

• Primary voters who closely follow politics & prefer extremists

• General election voters who are too ignorant of candidate positions—or too “intoxicated” by party loyalty—to vote for moderates over extremists

But our data tells a different story…

Apparently my work on ideology is coming up in TikToks to justify the idea that extreme positions gain votes.

For the record, I don't think my work indicates this.

Rather, it suggests that the most advantageous moderation is on the specific issues where a party is out of step with public opinion.

For the record, I don't think my work indicates this.

Rather, it suggests that the most advantageous moderation is on the specific issues where a party is out of step with public opinion.

Interesting that I’m not seeing takes that this will help Trump politically because 1) moving to the extremes will turn out his base and/or 2) economic reality doesn’t matter, only elite messaging about the economy. Makes you think.

Reposted by: David Broockman

I think Trump’s increasingly extreme trade policies will probably help the GOP electorally by juicing base turnout — the only way they could make this go better for themselves would be by banning abortion and privatizing Medicare.

The Berkeley Center for American Democracy is hiring a predoc next year. Please encourage any students interested in PhD study in political science to apply!

aprecruit.berkeley.edu/JPF04782

aprecruit.berkeley.edu/JPF04782

Junior or Assistant Specialist - Department of Political Science

University of California, Berkeley is hiring. Apply now!

aprecruit.berkeley.edu

Congrats to recent Berkeley PhD alum @annamikk.bsky.social on having her job market paper published at @apsrjournal.bsky.social!

www.cambridge.org/core/journal...

www.cambridge.org/core/journal...

White Democrats’ Growing Support for Black Politicians in the Era of the “Great Awokening” | American Political Science Review | Cambridge Core

White Democrats’ Growing Support for Black Politicians in the Era of the “Great Awokening”

www.cambridge.org

On the other hand, tying LIHTC funds to zoning helps the LIHTC funds go further.

It’s also a different situation in that LIHTC funds are limited & redistributing them doesn’t have the same issues as, eg, simply not building housing or semiconductor fabs does.

It’s also a different situation in that LIHTC funds are limited & redistributing them doesn’t have the same issues as, eg, simply not building housing or semiconductor fabs does.

I agree IZ on its own is not an example of everything bagel, it’s simply a bad idea. It becomes an everything bagel when it’s a requirement to access a good policy (streamlining).

The IZ example I think illustrates why the metaphor works. In CA, discretion is a problem and we need streamlining to build housing. The legislature wrote a streamlining bill to help build housing, but then decided you don’t get it unless you add in IZ. That undermines the streamlining’s core aim.