A solo show for @samaritans.bsky.social

Tickets here

www.redlionbooks.co.uk/product/poet...

Tell your friends

A solo show for @samaritans.bsky.social

Tickets here

www.redlionbooks.co.uk/product/poet...

Tell your friends

"On the edge"

On my unexpected week in hospital and five things I learnt about the state of the NHS.

(Free to read)

open.substack.com/pub/samf/p/o...

"On the edge"

On my unexpected week in hospital and five things I learnt about the state of the NHS.

(Free to read)

open.substack.com/pub/samf/p/o...

George Osborne bragged that his decision to raise the personal allowance meant loads of low-income people wouldn't pay income tax

Years later, that became a stick to beat them samf.substack.com/p/the-someth...

www.pcgamer.com/hardware/the...

www.pcgamer.com/hardware/the...

policyexchange.org.uk/publication/...

These are not new ideas, but they are bad ideas

A thread with some evidence

policyexchange.org.uk/publication/...

These are not new ideas, but they are bad ideas

A thread with some evidence

She might as well be doing a weather dance.

But this chart tells us almost nothing. Not comparing like-with-like ("social protection" ≠ DWP welfare spend).

And most of the difference driven by fact UK has (private) occupational pensions, other countries have state schemes

But this chart tells us almost nothing. Not comparing like-with-like ("social protection" ≠ DWP welfare spend).

And most of the difference driven by fact UK has (private) occupational pensions, other countries have state schemes

Basically, Britain is bad at management, it's fucking our economy, and politicians and journalists don't address it because they are the worst exemplars of it.

www.joxleywrites.jmoxley.co.uk/p/britain-ca...

Basically, Britain is bad at management, it's fucking our economy, and politicians and journalists don't address it because they are the worst exemplars of it.

www.joxleywrites.jmoxley.co.uk/p/britain-ca...

“Aggressive levels of mass migration have made us more divided... for example central Bradford - 50 per cent of people were born outside of the UK”, he said

Full story ⤵️

www.politics.co.uk/news/2025/05...

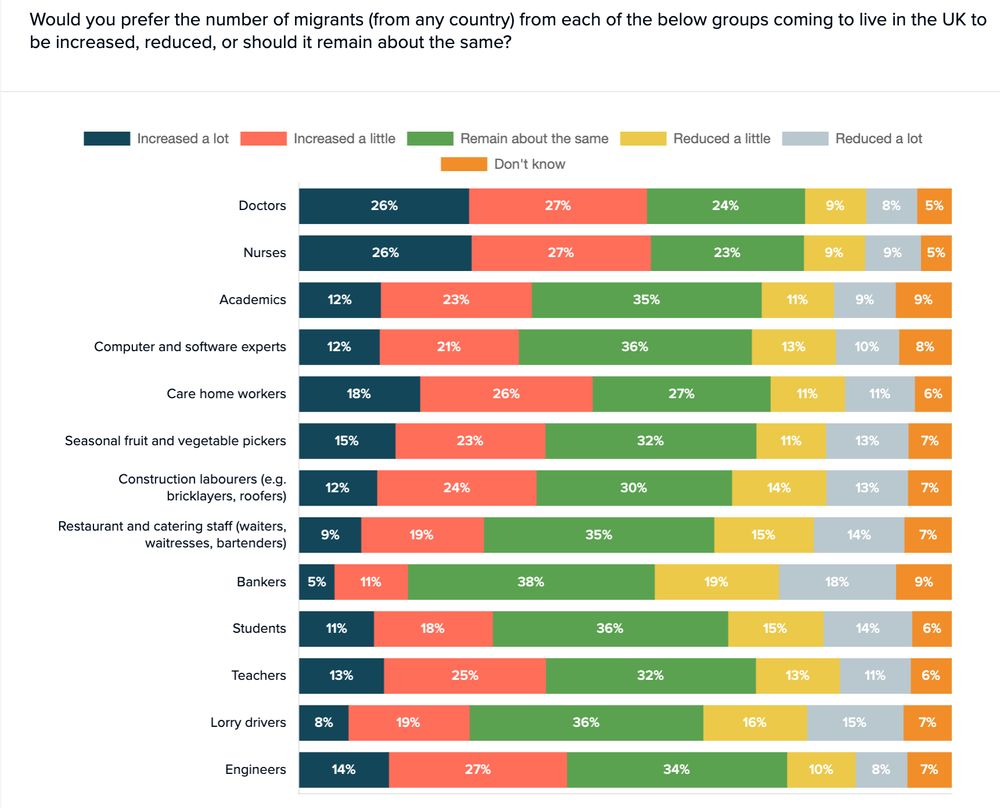

Increase the numbers: 44% (18% a lot, 26% a little)

Maintain current levels: 27%

Reduce the numbers: 22% (11% reduce a lot, 11% a little)

Focaldata for British Future (2nd - 6th May 2025)

www.britishfuture.org/white-paper-...